I think that’s self-deluding deceit and instead suggest that while many women have always been and continue to be kept subservient and often silenced, this has never stopped the literate actively writing about themselves.

Most people in many societies worldwide have come and disappeared without leaving much, bar a fading headstone or perhaps a tattered newspaper cutting. Even the hard work of modern ‘oral’ historians cannot make the humdrum and their lives more interesting or important than they were in reality. This is the true reason for ‘anonymity’. Let’s be honest - most of us live little lives of no lasting consequence!

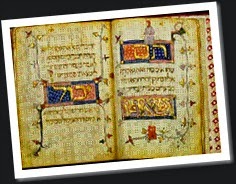

In earlier times Jewish women were often literate when many of their non-Jewish counterparts were not so fortunate. Such were sisters, Ella and Gella, two of the ten children of the Czech-born 17th-18th century Hebrew printer, Moses ben Abraham Avinu, who worked variously in Holland and Germany.

I insist that not only did the girls’ work for their father not go unrecognised, but that they actively ‘publicised’ themselves by their entries in the colophons (end notes) in several books they helped to typeset, where they asked to be forgiven any errors they may have made due to their young age!

I appreciate that my views are deeply heretical but I want to claim further that Moses ben Avraham was far more interesting than his children as, like his own father, Jacob, he was a convert to Judaism in a deeply antisemitic age. He was even imprisoned on one occasion for including allegedly anti-Christian passages in two books he printed.

The poem below, supposedly written by Gella aged eleven, was published in Written Out of History: Our Jewish Foremothers by Emily Taitz and Sondra Henry (1990).

The piece was used as a study passage at last week’s Masorti Women’s National Study Day in Jerusalem, when I argued that its content and tone make it far likelier that Gella wrote it as an adult from the viewpoint of an eleven-year-old. I’d love to know what anyone else thinks.

“Gella, aged 11, 1713(?)

“Of this beautiful prayer book from beginning to end,

I set all the letters in type with my own hands.

I, Gella, the daughter of Moses the printer, and whose mother was Freide, the daughter of R. Israel Katz, may his memory be for a blessing.

She bore me among ten children:

I am a maiden still somewhat under twelve years.

Be not surprised that I must work;

The tender and delicate daughter of Israel has been in exile for a long time.

One year passes and another comes

And we have not yet heard of any redemption.

We cry and beg of God each year

That our prayers may come before Him Blessed Be He,

For I must be silent.

I am (in) my father’s house (and) may not speak much.

As will happen to all Israel,

So may it also happen to us

For the Biblical verse says

All people will rejoice

Who lamented over the destruction of Jerusalem

And those who endured great sufferings in exile

Will have great joy at their redemption”.

© Natalie Wood (20 June 2014)

1 comment:

It has also been suggested that the translator of the original text (I'm unsure of the language - Hebrew/Yiddish/German?) may have themselves made the poem look more adult than how it first appeared.

Post a Comment